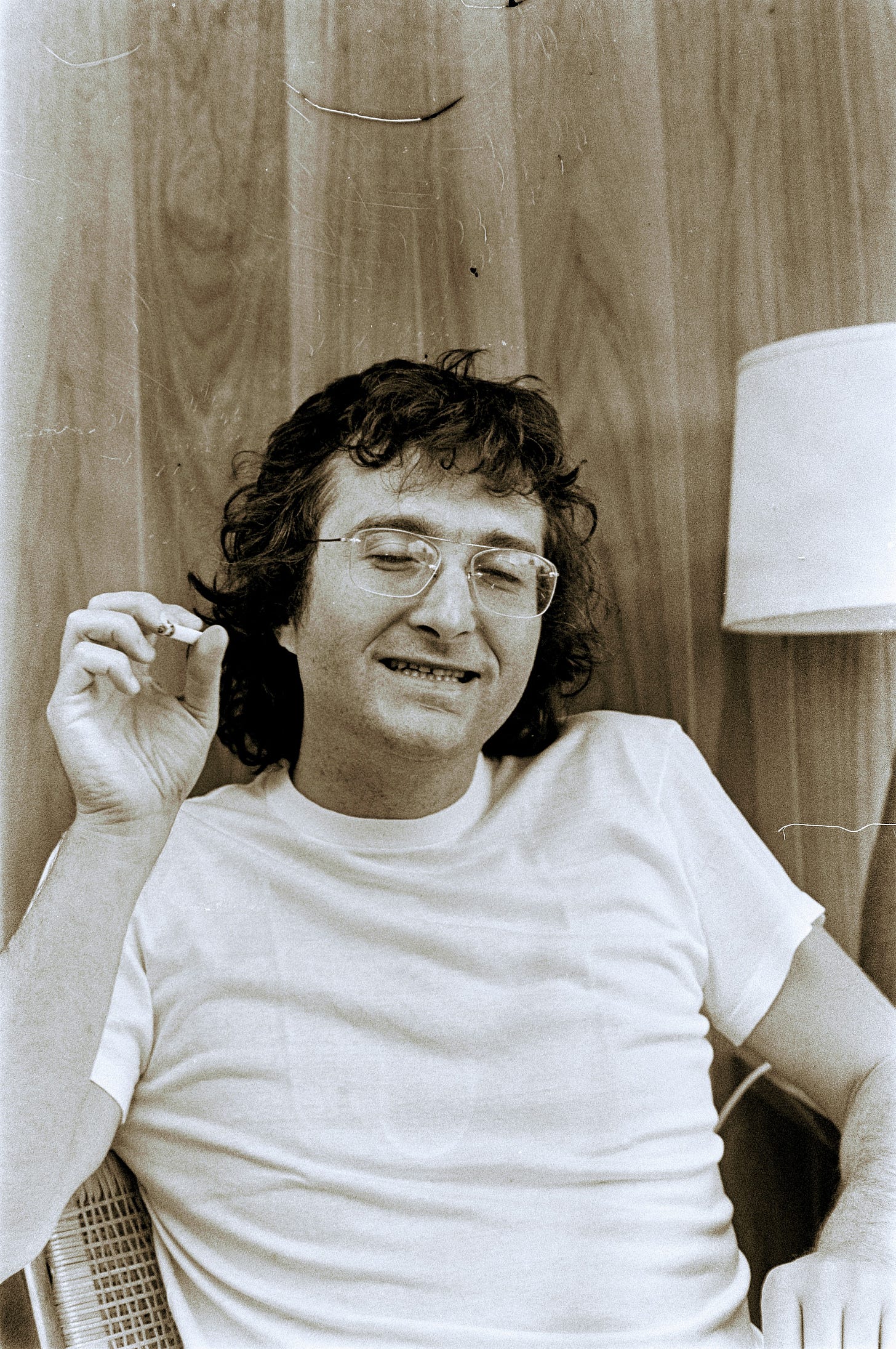

To hear the album Good Old Boys exactly right for the first time, you’d have to be about 20, driving straight south through eastern Missouri, possibly for Easter, and Randy Newman’s voice, who up till now you’d only heard sing about the intense toy friendship between a jealous cowboy and an emotionally unavailable spaceman, starts snarling through the speakers:

Last night, I saw Lester Maddox on a TV show

With some smart-ass New York Jew

And the Jew laughed at Lester Maddox

And the audience laughed at Lester Maddox too

I didn’t know anything about Lester Maddox, or who had laughed at him or why. But I learned, and I learned it from Randy Newman, who with the next three verses of “Rednecks” takes aim at the systemic racism of the South, right alongside the blatant hypocrisies of the moral North. Up until that point in my life, I didn’t know that one could do both things at once. And in a song? Forget about it.

Then, on the chorus, he sings:

We’re Rednecks, Rednecks

We don’t know our ass from a hole in the ground.

And then he says the N-word.

He says it a couple of times.

It’s shocking still today. But it’s how Randy Newman chose to begin Good Old Boys, an undeniably “capital A” American album, and an album that turned 50 this year. I have been listening to it for the last few months, mostly in the car on YouTube. I used to have a CD of it. In fact, I am not sure my copy of Good Old Boys ever came out of the 5-CD changer of my first car. (An ‘05 Ford Focus with what the guy at the garage diagnosed as a “serious” brake problem.)

Of the five albums pictured here, only the Good Old Boys CD is missing.

It may very well still be sitting in that car right now, wherever it wound up. Here’s an image: a Randy Newman CD, Good Old Boys, still intact, beyond the twisted metal of my compacted car in a junkyard not far from Des Moines.

What is Good Old Boys exactly? Think of it first as the complete antithesis of Waylon Jennings song of the same name, that early cell phone ringtone and theme song for The Dukes of Hazzard. On this Good Old Boys, Newman serves as anthropologist, spouting his findings from atop a piano bench. He uses the voices of bigots and drunks, folks in rotten marriages, full of grievances and rage, about being from the South, or poor, or white, or a combination of all of these, to try and tell us something about ourselves. Who we were. Where we’d come from. How we’d arrived at 1974.

Where we were heading.

I suppose the scene wasn’t all that different then today. Some of the words are even the same: Genocide. Watergate. Impeachment. But still, fifty years ago our parents got “The Rumble in the Jungle”, that great Foreman/Ali bout, broadcast live on pay-per-view on movie theater screens around the world. Now, we are offered Mike Tyson vs. Jake Paul streaming on Netflix, and sponsored by Celsius.

Heinous, really. Just heinous stuff.

Probably the most important things to know about Good Old Boys is that Randy Newman didn’t need to make this album.

By the mid-70s, he was already one of the most prolific and recorded songwriters working. One of his first songs,“They Tell Me It's Summer”, was recorded by The Fleetwoods when Newman was 19 years old. By 1974, his songs had been recorded across genres by Barbra Streisand, Dave Van Ronk, Judy Collins, Glen Campbell, the Everly Brothers, Nina Simone, and Wilson Pickett. Harry Nilsson had recorded an entire album of Newman’s songs, a gesture usually made towards the twilight of a songwriter’s career. Newman was 27 years old.

He’d had his first #1 hit in 1970 when Three Dog Night recorded “Mama Told Me (Not to Come).” (He’d even wrote a Dr. Pepper jingle.) Imagine Randy Newman walking into a Warner Bros. recording studio in Hollywood with the kind of sway then only given to financially successful songwriters, and choosing to make Good Old Boys.

He got studio legends Willie Weeks, Ry Cooder and Jim Keltner all to play on it, and even an assortment of Eagles to sing. Eventually, he premiered the album at the Symphony Hall in Atlanta. Randy Newman conducted the goddamn Atlanta Symphony Orchestra. Come on: he sang the album straight at them.

I believe that powerful forces at Pixar have long used their nefarious conglomerate means to stilt the popular recognition of Randy Newman’s long and storied solo career. As film composer, he’s scored nearly the entirety of Pixar’s animated fare, embedding himself deeply into millennial nostalgia in a way completely unique to him. Indeed if you look at the Spotify page for Good Old Boys, I can’t tell you how perplexing and unnerving it is to have a little green Mike Wazowski staring right out at you while you are listening to Randy Newman Sing, let’s say, “Every Man A King,” a song written by Louisiana governor, Huey "The Kingfish" Long.

Randy Newman has created a life in art that has allowed him to score the everyday soundtracks of several generations of the American family, while also allowing him to become one of the most caustic and accurate satirists of that very same America. Truly there has been no other artistic life quite like him in the modern era, to be both this well-known and at the same time, to also be this unheard.

Unpaired with a cartoon, the only songs that have carried over into the mainstream, or whatever access I seem to have to, are “Short People” and “I Love LA.” And perhaps maybe "It's a Jungle Out There," the theme song to the TV show Monk. (Sure, there were all those other hits he had for others, but I’m talking about Randy as both the songwriter and the performer here.)

“Early on, I decided I wasn’t a good subject for my songs, and I’d rather write about those types of people instead. Maybe that’s why my records weren’t more successful. People generally want songs about ‘I’ and ‘Me’ and ‘You’ and ‘We.’ They want things that are immediate, and my songs aren’t that — my stuff is slippery.”-Randy Newman interviewed in the New York Times

His songs are composed of scenes and characters fused from the surreal parts of Norman Rockwell paintings, and the sober parts of Gary Larson’s illustrations. I’ve come to see Good Old Boys as sort of a musical version of Winesburg, Ohio, written and sung by some drunken jester wedged beneath a piano and watching a television that has bunny ear antennae coming out of it.

Since the election, I can’t help but think about how the characters that Newman explored on this record now have descendants in contemporary American culture. Let’s face it: a pair of “good old boys” have secured the popular vote. And they did it to the tune of millions.

But other good old boys have been popping up for years. I recognized them at the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville. They showed up next to their pontoon boat in that Montgomery Riverfront brawl footage. Now, some of them even listen to that episode of The Joe Rogan Experience with Elon Musk without headphones on while they shop, slowly, through the grocery store.

Oh. And they hated the new Buzz Lightyear movie.

Good Old Boys began as a concept album centering around one Southern every man: Johnny Cutler. The album was to be called Johnny Cutler’s Birthday, and this recording features Newman narrating the scenes between the songs. Here’s Johnny Cutler at the city park. Here’s his wife. Here he is at the tavern. That sort of thing. (At one point he says, “Who the fuck am I talking to anyway? Who’s going to hear this?) It’s informal, feels private, and Newman rambles throughout. The tape catches him questioning himself, still trying to fit all the pieces together. The whole thing is absolutely exquisite.

I prefer this raw, early version of Good Old Boys, a thing much closer to Newman’s brutal and real intent than the actual one that was eventually released. The more I listen to Johnny Cutler’s Birthday, the more I’ve finally realized that it isn’t an album at all. It’s actually been another one of Newman’s film scores all along. His dark and angry vision of America wasn’t a prophetic one: he was simply making music about a part of America that has never gone away, a part that he knew would always exist.

I’m not sure if listening to Good Old Boys or Johnny Cutler’s Birthday is cathartic, exactly. At this point, I’m far beyond offering prescriptions of any kind. But this is the kind of gallows music that feels hopelessly appropriate now, in these short, anxious days, so quick to darken.

I’m sending this one out tonight from behind a desk in the dark somewhere out in an America that I can’t bring myself to recognize anymore, singing along with Randy Newman’s “Rollin’” towards a closed door with a mirror hanging on the back of it.

That’s my new address.

Here comes that last verse now:

Used to worry about wastin' time

And layin' round the house all day

But I'm all right now

I'm all right now

I never thought I'd make it

But I always do somehow

I'm all right

Rollin', rollin'

Ain't gonna worry no more…

Additional Good Old Boys links:

There’s an episode of Malcolm Gladwell’s Revisionist History where he uses the album, and “Rednecks,” in particular as a gateway into the history of Lester Maddox and the American South.

“Randy Newman Is at His Best When America Is at Its Worst”-New York Times

- ’s review from his ‘70s Consumer Guide.

I am grateful to be a member of the Iowa Writers’ Collaborative.

Seeing his name on the songwriting credits of some of my CDs has inspired some thinking on my part- how can the Pixar man have also written very adult-in-nature songs like "You Can Keep Your Hat On" and "Mama Told Me (Not To Come)"?

Thank you for this. It's the album that can't be played in public, for anyone. But it might be one of our most important self-portraits. The infuriating, 10-cent Will Sasso impression of Newman on MadTV, then Family Guy, has further infantilized the image of Newman to mouth-breathing America, but they were never going to get his point anyway.